Podcast (lead-with-a-story-podcast-series): Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: RSS

In early 2001, the stock market was still reeling from the dot-com bubble and burst a few months earlier. The economy was uncertain, and even many traditional companies were in turbulent times. Procter & Gamble was one of them.

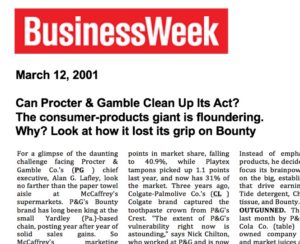

It had been less than a year since the company’s stock had lost nearly 40 percent of its value in a single week of trading. The business press was quickly losing its love affair with Internet start-ups and returning its interest to conventional businesses. So BusinessWeek decided to do a story on what went wrong with P&G.

After asking for an interview with a P&G official, BusinessWeek was offered Tarang Amin, the newly appointed marketing director of P&G’s Bounty paper towel franchise. The brand had just finished a tough year. Tarang represented a fresh and unbiased pair of eyes to talk about Bounty’s history and plans. A few uneventful weeks went by after the interview while the reporter continued researching the article.

After asking for an interview with a P&G official, BusinessWeek was offered Tarang Amin, the newly appointed marketing director of P&G’s Bounty paper towel franchise. The brand had just finished a tough year. Tarang represented a fresh and unbiased pair of eyes to talk about Bounty’s history and plans. A few uneventful weeks went by after the interview while the reporter continued researching the article.

On March 12, 2001, the article hit the newsstands, and Tarang got his first look. The title was Can Procter & Gamble Clean Up Its Act? The first sentence said, “For a glimpse of the daunting task facing P&G’s chief executive, look no farther than the paper towel aisle.”

That first line hit Tarang right between the eyes. The article stated that Bounty had lost more market share in the past year than any of P&G’s top brands. It went on to outline an opinion of everything the brand had done wrong in humbling detail: getting beat on product and cost innovation by its competitors, cutting its advertising spending, raising prices too much, and cutting back its in-store sales force. The article even accused P&G of rotating through brand managers too quickly.

That first line hit Tarang right between the eyes. The article stated that Bounty had lost more market share in the past year than any of P&G’s top brands. It went on to outline an opinion of everything the brand had done wrong in humbling detail: getting beat on product and cost innovation by its competitors, cutting its advertising spending, raising prices too much, and cutting back its in-store sales force. The article even accused P&G of rotating through brand managers too quickly.

Tarang was crestfallen. Although he was expecting a negative article, the story was much worse than he had thought. It would surely disappoint and possibly even embarrass the hundreds of employees who work to make and market the Bounty brand. More importantly, having it come out while they were in the middle of the turnaround risked undermining the plan and having people lose confidence in what they were doing. His only hope was that nobody would read the article and it would just pass over unnoticed. That hope was dashed when he arrived home at the end of the day and stepped out of his car. His next-door neighbor yelled over the hedge, “Hey, Tarang, that was a terrible article about you today, huh?”

That evening, as Tarang mulled over the article, he thought about writing a letter to the editor to complain about some of the facts that maybe weren’t quite right, or statements that seemed out of context. But he thought better of it. The thought of going to work the next day and facing his teammates was overwhelming. What he really wanted to do was bury his head in the sand and pretend none of it ever happened.

What he did instead was to write a memo to everyone on the team, which he titled Bounty BusinessWeek Article—My Perspective. In it, Tarang admitted he was originally disappointed in the article, knowing how hard everyone on the brand had been working in the past year to put the business back on track. Yet, he had to admit, many of the points in the article were correct. For example, “We did let our price get out of target range,” and some of “our key innovations didn’t make it to market.” In fact, several of the points laid out in the article were exactly what the brand had identified itself in defining its new strategy to return to growth.

Therefore, rather than get defensive, Tarang insisted people view this article as reinforcement that they knew exactly what their issues were and how to fix them. He reminded them of their plans to return to innovation leadership, and that they had already lowered Bounty’s price to be more competitive. He concluded the memo by restating his confidence in the people and plans and his aspiration to make their great brand even greater in the year ahead.

Tarang’s memo quickly circulated around the building, at first among Bounty team members but soon to other teams. His general manager sent it to the most senior executives in the company, many of whom forwarded it to people on their brands as well. Their purpose in sharing it broadly was primarily to give a response to the questions on everyone’s mind, “What does management think about this article and what are we doing about Bounty’s situation?” It answered both those questions brilliantly. But it did something even more important, I think. It showed business leaders how to turn a demoralizing event into a critical agent of change.

Over the next few months, and even years, that BusinessWeek article—and Tarang’s response—would get pulled back out of the file drawers. They served as a rallying cry for change. In the decade after that article was published, Bounty’s market grew 10 points, to 46 percent, and the brand’s sales grew by two-thirds.

Today, as Chairman and CEO of e.l.f. Cosmetics, Tarang Amin tells that story to colleagues when they’re going through a tough or embarrassing situation and they want to hide under a rock. The lesson they learn is to not hide from it. Instead, publicize it. Turn it to their advantage. Use it as a tool for change and galvanize the organization around it.

[You can find this and over 100 other inspiring leadership stories in my book, Lead with a Story.]

—

Paul Smith is one of the world’s leading experts on business storytelling. He’s a keynote speaker, storytelling coach, and bestselling author of the books Lead with a Story, Parenting with a Story, and Sell with a Story.

Paul Smith is one of the world’s leading experts on business storytelling. He’s a keynote speaker, storytelling coach, and bestselling author of the books Lead with a Story, Parenting with a Story, and Sell with a Story.

Connect with him via email here.

Connect with him via email here.

Follow him on Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, and Instagram.

Sign up for his newsletter here to get one new story a week delivered to your inbox.