The following is an example of both storytelling with data and a story that’s kicked off with a mystery — one of the most effective story starters you’ll find.

IN THE SUMMER OF 2000, I worked in P&G’s diaper business, where we make and market the Pampers and Luvs brands. I was given a unique opportunity that summer to develop and present a five-year strategy recommendation to the president and leadership team.

After a few weeks of intense analysis and preparation, I had my big moment with leadership. They were probably expecting a traditional P&G-style presentation where I would stand up, tell them what my recommendation was, and then justify that recommendation with the details of my analysis. But that’s not what I did. Instead, I told them the following.

“Every one of you in this room has been taught since you joined the company that if you deliver the sales volume, the profits will follow. And our strategy in this business unit reflects that belief. All of our plans are directed at selling more diapers. Period. So in preparation for this meeting, I decided to do some research to find out if that assumption was true.

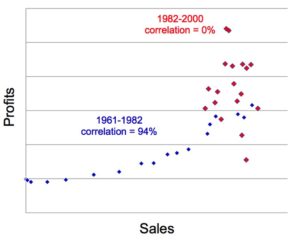

“I looked back over our nearly 40-year history making disposable diapers in the United States and here’s what I found. For the first 21 years, 1961 to 1982, there was a near perfect correlation between sales volume and profits. Every year as sales went up, profits went up. When sales went down, profits went down. It seems that assumption about higher sales leading to higher profits was true, and these data are probably the reason why we’d all been taught this mantra.

“But if you look at the data since 1982, they tell a very different story. For the past 18 years, 1983 to 2000, there has been absolutely no correlation between sales volume and profits whatsoever. None. Over those 18 years, profit growth years have been just as likely to accompany sales growth as sales declines. The same is true for profit declines.”

The scatter plot of this data is shocking, so I showed it and paused there while the audience took it in. I then asked the audience this question: “What do you think could have happened in 1983 that forever changed the nature of this higher-sales-equals-higher-profits industry?”

The scatter plot of this data is shocking, so I showed it and paused there while the audience took it in. I then asked the audience this question: “What do you think could have happened in 1983 that forever changed the nature of this higher-sales-equals-higher-profits industry?”

Someone answered, “Is that when Kimberly-Clark launched Huggies?” “No, but good guess,” I responded. “They launched several years prior to that. Any other ideas?”

“Is that when commodity costs got out of control?” someone offered. “Another good guess,” I said. “That happened in the late seventies. . . . Anyone else?”

I continued to let the audience throw out guesses until someone started getting close by asking about consumer behavior. I encouraged them to keep thinking along that direction, and steered the conversation closer with each following idea until someone found it.

“Is that maybe when the market reached full penetration?”

“Bingo!” I yelled. “That’s it! Before we launched disposable diapers in the early sixties, the U.S. diaper market was composed entirely of cloth diapers that moms had to wash and reuse. Every year thereafter, more and more moms began to try disposable diapers and abandon the drudgery of cleaning dirty cloth diapers.”

By 1983, the market for disposable diapers had essentially reached 100 percent of households with kids who wore diapers, and cloth diapers had almost entirely vanished from the marketplace. Up to that point, everyone making disposable diapers had rapidly growing sales numbers, and the rapidly growing profit numbers to go with them. A rising tide lifts all boats. (The cloth diaper makers, of course, were going out of business.)

But in 1983, all of that changed. Once we had successfully converted every mom in the country to using disposable diapers, the total industry sales of disposable diapers stopped growing every year, and largely flattened out. The disposable diaper business in the United States went from what P&G would call a “developing market” to a “developed market” in 1983. And apparently, we failed to notice it. We were still following the same basic “sell more” strategy we had followed during the developing-marketperiod. An appropriate business strategy for a developed market is usually very different. And my audience knew it.

All of these conclusions—my conclusions—immediately flowed from the mouths of the audience like a well-rehearsed screenplay as soon as someone correctly identified the key observation I wanted them to spot. My conclusions had become their conclusions. Within a few minutes, my recommendations became their recommendations. Success.

I could have given them the standard-form presentation with recommendation up front. But instead, I took them on a journey so they could experience the same eye-opening discovery moment I had weeks earlier as part of my research. That “ah-ha” moment leaves a powerful mental and emotional marker in human memory.

But this “discovery journey” has another benefit, too. People are naturally more committed to their ideas than they are to your ideas. This story technique turns your ideas into their ideas. Using it, your audience will be more likely to remember your ideas, be moved by them, and passionately pursue them. As a result, the discovery journey story is one of the most effective techniques I’ve found for making recommendations that get accepted and acted upon.

Source: Lead with a Story: How to Craft Business Narratives that Captivate, Convince, and Inspire, by Paul Smith.

—

Paul Smith is one of the world’s leading experts on business storytelling. He’s a keynote speaker, storytelling coach, and bestselling author of the books Lead with a Story, Parenting with a Story, and Sell with a Story.

Paul Smith is one of the world’s leading experts on business storytelling. He’s a keynote speaker, storytelling coach, and bestselling author of the books Lead with a Story, Parenting with a Story, and Sell with a Story.

Connect with him via email here.

Connect with him via email here.

Follow him on Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, and Instagram.

Sign up for his newsletter here to get one new story a week delivered to your inbox.