Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: RSS

Podcast (lead-with-a-story-podcast-series): Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: RSS

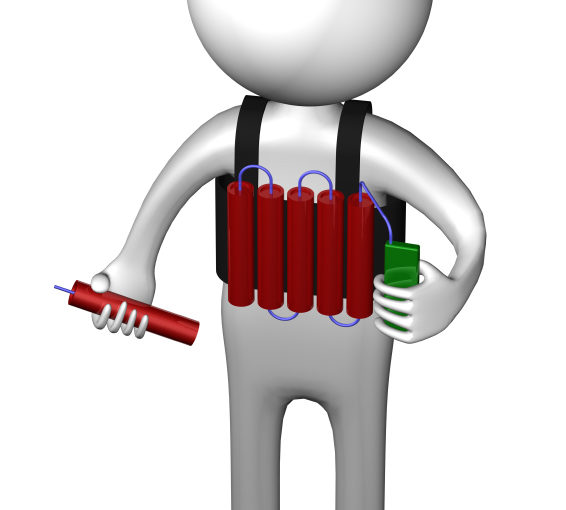

Part of dealing with issues of race and prejudice in a healthy manner starts with recognizing that we all have deep-seated preconceived notions about others. Some we’re conscious of and know how we got them, and others we’re not. But both can and do affect how we view and interact with other people. A university professor we’ll call Karen learned that the hard way when she had to face her own preconceived notions. But in her case, that preconceived notion walked into her class one day with a bomb strapped to his chest.

Karen is the department chair of women’s studies at a large midwestern university. One fall, already a week into the semester, a man of Middle Eastern descent walked into her office. We’ll call him Saeed. Saeed was in his late twenties, had just arrived in the country, and was asking permission to enroll in Karen’s Introduction to Women’s Studies class. Typically, 75 percent of the students in that course are female. And she’d never had a man from the Middle East take the class before.

Looking back, she admits her first thought was, “This is going to be a tough semester. He’s going to challenge everything I say. And it’s certainly going to be awkward when I talk about how women aren’t allowed to drive in some Middle Eastern countries.” She could already picture him rolling his eyes when she discussed modern views about women that would contradict conventional wisdom where he’s from.

Well, despite those misgivings, she let him into her class anyway. And as soon as he left her office, she started having pangs of guilt over her quiet reservations. She said,

I hated myself for it almost immediately. Honestly, I just met this man. I had no evidence to make those kinds of assumptions.”

As early as the next week of classes, she started to get a picture of what Saeed was like as a student. And it was nothing like what she expected. “He was respectful, interested, engaged, and very bright.” She said, “He even brought me a copy of the Qur’an with all the passages about women highlighted to help me understand women’s issues in his culture. And there wasn’t a single day he didn’t talk to me after class about how it was relevant to his culture and what he was trying to accomplish.”

And what he was trying to accomplish was even more impressive than his in-class behavior. Saeed had arrived in the United States with his wife, who was getting a master’s degree and had plans to continue toward a Ph.D. They wanted to return to their home country when their studies were complete to provide an example of what an educated Muslim woman can accomplish and to show that it’s possible to be both a good Muslim woman and educated. He was taking this class to help him prepare for that journey.

Karen’s perception of Saeed had taken a radical turn for the better in a short eight weeks. She really had been too quick to judge him. He was truly the ideal student. Or so she thought, until one morning he walked into her class with a bomb strapped to his chest.

Despite the bulky jacket covered in explosives, the combat fatigues instead of pressed pants, and the uncharacteristic look on his face, she of course recognized Saeed immediately. But what on earth was behind this? What would cause her ideal student to turn into a terrorist overnight? Or was it worse? Was the entire eight weeks of class all a ruse and this was Saeed’s real plan all along?

She didn’t have to wait long to find out. It turned out that the cause of this sudden change in behavior in Saeed was the same thing that caused Karen to presume he’d be such a troublemaker as a student. In fact, the cause of his decision to strap a bomb to his chest wasn’t something inside Saeed. It was something inside Karen. And she realized that the moment she bolted upright in bed in a cold sweat to find that the bomb scare was nothing but a nightmare.

Karen relaxed. There was no bomb and her student was no bomber. He was the fine upstanding student she had come to know and appreciate over the first half of the semester. But then she had to ask herself, “Why would I have had such a dream? For the last two months he’d shown me nothing to give me the impression he would do anything of the sort.” Quite the opposite. He was one of her favorite students.

The lesson

She concluded two things from this. First, while there was absolutely no association in her conscious mind between suicide bombers and Saeed, clearly in her subconscious mind there was.

Second, she concluded we’re probably all susceptible to making judgments about people based on stereotypes and deep-seated preconceived notions. Of all people to have had this experience, she is a professor of not just women’s studies, but also courses on race, class, and gender. She teaches awareness of these issues for a living! She of all people should be as free from those kind biases as possible. Yet twice in two months she suffered one bout of consciously biased thoughts of Saeed and one disturbing subconscious one.

And if you’re honest with yourselves, some of you reading this will admit that somewhere two paragraphs ago, you thought to yourself, “See! She was right to begin with. She should have never let this guy into her class!”

“You have to be vigilant,” Karen advises. “When you see it creep into your consciousness, confront it. None of us are immune.”

Here are a few questions you might want to think about and share with your coworkers.

- Were you more surprised when you read that Saeed walked into the class with a bomb strapped to his chest, or more surprised when you realized it was just a dream?

- Have you ever gotten to know someone and they turned out to be nothing like you thought they would? Who was it?

- How could Karen’s conscious or unconscious biases toward Saeed have affected her behavior and role as his professor?

- What might be a legitimate use of statistical profiling or stereotyping?

[You can find this and over 100 other character-building stories in my book, Parenting with a Story.]

—

Paul Smith is one of the world’s leading experts on business storytelling. He’s a keynote speaker, storytelling coach, and bestselling author of the books Lead with a Story and Parenting with a Story.

Paul Smith is one of the world’s leading experts on business storytelling. He’s a keynote speaker, storytelling coach, and bestselling author of the books Lead with a Story and Parenting with a Story.

Connect with him via email here.

Connect with him via email here.

Follow him on Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter.

Sign up for his newsletter here to get one new story a week delivered to your inbox.

Via email from Reader, Lee Bowman: I love this story, but not because of how it might speak to our prejudices and biases; but how it speaks to the infinite limits of the human mind and the specific impacts of what we say and do versus what we think.

Should anyone care what transpired in the quiet infinity of Karen’s mind? Her thoughts about the safety and implications of this one student could have transpired in a sub-nanosecond. What did she think about the football player, the fashionista, the doctoral chemical engineer in his lab coat and all the others in her class. If she noticed them, surely she had a scope of thoughts based on experience, knowledge and biases! She made good choices, had a bad dream and probably worried unnecessarily about having a bad thought.

To notice is to think, and then to think is to consider all the possibilities. Possibilities bring a mix of risk and benefit, but what really matters is what do (which includes what we say)! The actual decision and choice of how we act is what really matters and how it translates into action (instead of possibilities). I say this because of your book (which I will soon buy) on parenting with a story! Should we be held accountable for what we think (or make our children feel guilty for what they think), because the emotional damage, guilt and resulting functional limitations could be tremendous. Our kid’s decisions will be their path to their destiny and choices between thoughts will drive that.

When I was 10 years old, I lived in a rust belt, WASPy manufacturing small town. Most of our town citizens were lacking in what we now call diversity, but the small minority population of blacks and Hispanics lived in a certain section of town and other than at the city pool in the summer I had very little day to day exposure to these people of color. That school year we began the small town version of busing and I had no clue as to the what or why of that action, other than I changed to a different elementary school that I still walked to every morning. My classes were ‘integrated’ and the beauty of being young and naïve was that all my classmates were just classmates although several were Hispanic (fraternal twins, Jonny and Frankie) and several were black (Lee, Bruce and Kim). Thru the school year, I came to know that Jonny and Frankie were what we called ‘tough’ kids who came from a terrible family situation and aside from playing football at recess; the pretty much kept to themselves.

That summer at the city pool, I saw the both of them while I sat on picnic table and was using my pocketknife to cut the top off a plastic covered popsicle. They came over to me and although initially friendly, they were transfixed on the pocketknife. When they asked to see it, I gave it to them and after a few minutes of carving on the old picnic table and doing what kids do with pocketknives; they did something else. First Jonny and then Frankie held it my stomach and asked if I would buy them a popsicle too or else they would cut me. I did not have enough money left and after they took what I had and drew blood; I had the chance to run and I did. I was terrified at that moment and they so delighted in my terror that they made sure to shout and get my attention whenever I saw them be it at the pool or at school the next fall. Thankfully, they were held back and not in my class the next school year, but they tormented me whenever they had the chance and I knew the sound of their voice (and their accent) anytime and everywhere.

Thru high school I saw them increasingly little as they were poor students and as might be expected, they were prone to suspension from school and took classes out of school in vocational training. My senior year, they were convicted of breaking into an elderly women’s apartment, stabbing the woman 98 times and killing her for a handful of dollars. They are serving a life sentence behind bars now, but what does a person learn from such an experience?

More than forty years later, I am currently living in a much larger Midwestern town. The nearly 7 years of possible but sporadic tormenting have produced a number of anxieties in adulthood, but my ‘choice’ is to live free and I attend a Catholic church which is nearly 50% Hispanic. No one should be privy to the thoughts that go thru my head on rare occasions, but the mind is infinite in possibilities and under the right circumstances I can get a very good startle. I choose to have friends and colleagues across the rainbow, but I choose to NOT carry a pocketknife!

I hope all of our kids grow up to not fear their own thoughts, be confident in their decisions, make good choices based on their knowledge of things and people while “judging not lest they be judged”.

Have loved your class, book and these columns! Have a Merry Christmas and peaceful happy new year!