Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: RSS

Podcast (parenting-with-a-story-podcast-series): Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: RSS

If you don’t have your health, nothing else in life seems to matter much. But when we do have our health—or at least think we do—it’s often easy to neglect it and take that good health for granted. But that’s when the seeds of destruction are usually sown. One person who knows that well is David Casterline.

If you don’t have your health, nothing else in life seems to matter much. But when we do have our health—or at least think we do—it’s often easy to neglect it and take that good health for granted. But that’s when the seeds of destruction are usually sown. One person who knows that well is David Casterline.

The big race

March 23, 2013, was a big day for David. Along with 3 or 4 of his coworkers, he’d signed up to run a 33.5-mile relay race for a local charity in Kalamazoo, Michigan. David drew the last leg, so he’d be running the final five miles of the race.

Now David’s an active fifty-two-year-old, and in pretty good shape. He’s not too experienced of a runner, but he did run a 5K race the year before. So he was confident he’d do okay.

It was cold and muddy that morning. So that made the run even harder. And when it was David’s turn, he found most of his leg was uphill, even the final sprint to the end. But he attacked it like a champ, and finished his leg in just over forty minutes. If you know anything about running, thats an impressive time for an experienced runner, much less a novice.

So as you might expect, he crossed the finish line breathing heavy and feeling a bit lightheaded. Typical for someone running a longer distance and a faster pace than they’re used to. He even stumbled into a pole when he wasn’t looking where he was going. It wasn’t too embarrassing, though. It’s hard to focus when you’ve just run five miles uphill and you’re still trying to catch your breath.

Half an hour later, he met up with his team at a local restaurant to celebrate. In addition to finishing a 33.5-mile race, they raised more than $9,000 for the local charity, so both good causes for celebration.

Well at lunch somebody noticed that David didn’t look very good. His lips were still blue from the cold, even though they were inside now. So they asked him, “David, are you still dizzy?”

“Yeah. A little.” he said.

“Sick to your stomach? Breathing a little fast?”

“Yeah, those too.”

David, you’re dehydrated. Those are the classic signs.

“You didn’t get enough liquid in the race. Drink some water. Better yet, have some Gatorade.”

You know, it is a typical mistake for a rookie runner to make: Not hydrating enough before, during, and after the race. Now he was paying the price. But he was catching up with fluids now, so it should get better soon. What he was too embarrassed to say at the time was that he was really feeling the effects of the race in the muscles of his arms and chest. He’d prepared for a tough leg workout. But he didn’t expect all the pumping of his arms during the sprint at the end would take so much out of him. Now he was cramping a little.

On the way home. . .

Well, after lunch some of his friends were kind enough to drive David home, even though he was feeling better by then. On the way they called his wife, Val, just to let her know he wasn’t feeling well and they were bringing him home. They described all his symptoms. But David talked to her and assured her that he was fine. Already feeling better. “Next time I’ll train better for the race. And drink more water.”

Well, that worried Val. When they hung up, she called both their sons, Matt and Chris. Both were ninety miles away at college studying medicine, but were far enough along in their studies to help alleviate their mom’s unnecessary worrying. She just needed someone to tell her that David was going to be fine. Val relayed everything she’d been told to both boys. After talking to each of them on separate phone calls, they both came to the same conclusion and told their mom the same thing. So she he had her answer.

When David got home a few minutes later. . .

Val met him at the door. But instead of a hug and a kiss, she said very directly “David, you need to go to the hospital. You’re having a heart attack.”

Now what David was thinking was, “Ugggghh. . . I was afraid she’d say that. It’s typical of the people that love us most to overreact to the smallest things.

“No, no, Val. I’m fine. Really. Look at me . . . I’m fine.”

But Val still wasn’t convinced. She got her boys back on the phone and talking directly to David. She thought, “If he won’t listen to me, maybe he’ll listen to them,”

So for several minutes both boys tried to convince their dad to go to the hospital. And with the same pride and stubbornness most men would show in the same situation, he resisted. But two things stand clear in his memory today from that phone call. First, the stark distinction of being told that just because he was feeling better didn’t mean he was getting better. In fact, one of them said, “You didn’t have a heart attack, Dad. You’re having a heart attack right now! It’s still happening.”

The second thing he recalls is either a promise or a threat, depending on how you look at it. They said, “Dad, if you don’t get in the car right now and go to the hospital, we’re driving home and taking you ourselves, whether you’re willing to or not.” And at twenty-one and twenty-three years old, both boys were very capable of delivering on that threat, and David knew it. So whether it was to avoid a messy confrontation or just to appease his family, David let his wife drive him to the local hospital.

At the hospital. . .

A few tests later and the doctors confirmed, “Mr. Casterline, you’ve had a major heart event. We’re sending you to Borgess Hospital in Kalamazoo. They have better facilities for this.”

David was thinking “Can this really be happening to me? I feel much better now. Why is everyone making such a big deal out of this?” And by then it was pretty late at night, so he asked the doctor, “Look, do I need to stay here tonight? Or can I at least sleep at home in my own bed and go to Borgess tomorrow when you get me an appointment?”

“Mr. Casterline. You don’t understand. You’re going right now. The ambulance is pulling around front as we speak.”

Thirty minutes later at Borgess, David was rapidly assessed and treated. I’ll spare you the details of that now. But at approximately 1 a.m., when the danger had passed and the treatment was bringing David’s vital signs back to safe levels, the doctor stopped by to talk. David told him about the lengths his wife and boys went through to get him to come in. And that’s when the severity of his situation became clear for the first time. The doctor said,

David, if they hadn’t gotten you to come in, by morning you’d be dead.

Those words hung in the air for a somber moment. David could not believe how close he had come to not going to the hospital, how close he had come to losing everything. He clearly owed his wife a debt of gratitude. And to his boys, who had become the parents in this situation, he could not be more grateful and proud at the same time.

Now Thanks to good teachers and public health campaigns, these days just about everyone knows the symptoms of a heart attack: pain or discomfort in the chest or arms, shortness of breath, lightheadedness, and nausea. But there are problems with that description. First, lots of medical problems cause some of the same symptoms, like dehydration. But the other problem is this: If you were having those symptoms yourself, you probably wouldn’t think of them in such terse, clinical terms. “Oh my, I’m having ‘shortness of breath’ and ‘nausea.’” In fact, you’re probably not thinking in words at all. You’re thinking in feelings. And what you’re feeling at that moment is that you’re having trouble catching your breath and feel like you might throw up.

The other thing you’re feeling is a desperate need to convince yourself (and anyone else who will listen) that you’re just fine. Having a heart attack is embarrassing. Only “old and out-of-shape people” have heart attacks, right? Not me. I’m too healthy for that. That’s just what David thought too.

What I decided to do about it

Now I have to admit, out of over 200 people I’ve interviewed in the last few years as part of my research on storytelling, David’s story is one that resonated with me personally more than almost any other. I’m just a few years younger than him, we’re both in decent shape, I also have 2 boys, and I occasionally run a road race. It was just obvious listening to his story that it could have just as easily been me. The only difference is that my sons aren’t old enough to be in medical school or to drag me off to the hospital against my will. So if it had been me instead of him, I might not be alive today. And that scared me.

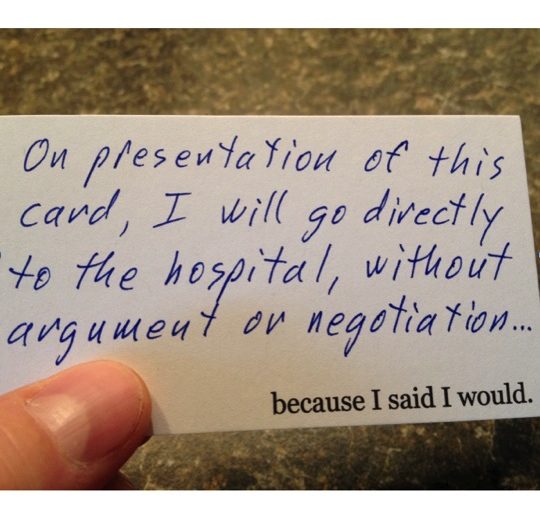

So when my sons got home from school that day, I did two things. First, I told them David’s story. Every last detail. Second, I gave them each a wallet-sized card where I’d written the following words. . . “On presentation of this card, I will to directly to the hospital, without argument or negotiation . . . because I said I would.”

So when my sons got home from school that day, I did two things. First, I told them David’s story. Every last detail. Second, I gave them each a wallet-sized card where I’d written the following words. . . “On presentation of this card, I will to directly to the hospital, without argument or negotiation . . . because I said I would.”

I made that card for them because I don’t want to be that guy that dies because he’s too proud and stubborn to go the hospital. That card gives them permission to send me to the hospital, even against my will. And it gives my ego permission to go without feeling like an out-of-shape old man. I’d just be going to make my kid happy.

So here’s the challenge: I challenge every parent listening to this to do the same.

First, share David’s story with them. They need to hear the details of what a heart attack looks like in the real world. If you grab your chest and fall to the ground gasping for breath like in the movies, you don’t need a card like this. You’ll be begging them to call 911. But if it happens to you like it happened to David—in the covert, confusing, ambiguous, and embarrassing way they often happen in the real world of a busy workday or tennis match or road race—that’s when you’ll need someone close to you to have have heard this story.

Second, make them your own card with similar words. You can get a free set of blank cards printed only with the words “because I said I would” at the bottom from www.becauseisaidiwould.com. The founder of the organization, Alex Sheen, and his supporters provide the cards to encourage people to make worthy promises to people they love, and then to keep those promises.

Can you think of a more worthy promise than this?

[You can find this and over 100 other character-building stories in my book, Parenting with a Story.]

—

Paul Smith is a one of the world’s leading experts on business storytelling. He’s a keynote speaker, storytelling coach, and bestselling author of the books Lead with a Story and Parenting with a Story.

Paul Smith is a one of the world’s leading experts on business storytelling. He’s a keynote speaker, storytelling coach, and bestselling author of the books Lead with a Story and Parenting with a Story.

Connect with him via email here.

Connect with him via email here.

Follow him on Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter.

Sign up for his newsletter here to get one new story a week delivered to your inbox.